What happens when the American Dream becomes a dangerous obsession?

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) plunges readers into the heart of the Jazz Age, a world shimmering with promise yet shadowed by disillusionment.

We meet the magnetic Jay Gatsby through narrator Nick Carraway’s eyes on Long Island’s opulent shores in 1922. Gatsby’s legendary parties and vast wealth merely disguise an all-consuming quest: to resurrect a cherished moment from his past and reclaim the love of Daisy Buchanan.

Is Gatsby’s dream truly romantic, or symptomatic of deeper societal fractures? Our analysis of The Great Gatsby argues that Fitzgerald masterfully crafts the novel as a profound elegy for a corrupted American Dream. The novel reveals how the dream’s potential is decimated by the unyielding realities of American social class and a destructive obsession with an idealized, irrecoverable past.

Examining Fitzgerald’s intricate narrative, potent symbolism, and unforgettable characters reveals layers of sharp critique beneath the novel’s glittering surface, which are further explored in our comprehensive plot summary.

The Dream Reimagined: Gatsby’s Material Illusion

Jay Gatsby’s transformation from the impoverished James Gatz initially seems to fulfill the American promise of self-realization. His ambition, however, demands far more than prosperity; wealth becomes the crucial engine driving an elaborate illusion, a meticulously constructed stage designed purely to recapture Daisy.

Therein lies a central irony: Gatsby seeks to recreate a genuine past moment through a completely fabricated present. His vision is intensely nostalgic, attempting to weld an idealized past onto a resistant present, tragically misreading the nature of time and love.

His fortune’s criminal origins, linked to the shadowy Meyer Wolfsheim, immediately taint this pursuit, revealing that the glittering path to Jazz Age wealth often required moral compromise, yet failed to guarantee acceptance among the established elite.

Gatsby surrounds himself with potent symbols of success: the sprawling mansion mimicking European aristocracy, the gleaming hydroplane, the vibrant rainbow of expensive shirts. He believes these tangible markers can somehow secure his intangible desire for Daisy’s past affection.

His legendary parties, overflowing with anonymous guests drawn by spectacle, are more carefully staged productions than celebrations. These vast, impersonal gatherings become nets cast, hoping to catch Daisy’s fleeting attention.

Jordan Baker’s cynical observation that only large parties offer privacy (“at small parties there isn’t any privacy”) subtly underscores the loneliness inherent in Gatsby’s performative world, foreshadowing his sparsely attended funeral.

Even his impressive library reveals the performance. Filled with real but pointedly uncut books, it is, as Owl Eyes drunkenly perceives, a masterful facade of cultivated depth. Gatsby’s authentic, humble beginnings remain buried beneath the glamorous, fabricated present he performs.

The Unyielding Barrier: Social Class in the Jazz Age

Fitzgerald depicts the divisions of American society as an invisible force field across the Long Island Sound. East Egg, the domain of the Buchanans, represents the entrenched power of inherited “old money.” This aristocracy displays inherited confidence, adheres to established social codes, and exhibits a chilling carelessness born of a privileged birthright.

Tom Buchanan, physically imposing yet intellectually insecure, having perhaps finished only one book (the fashionable racist tome The Rise of the Colored Empires), aggressively patrols the borders of this exclusive world. His authority rests not on culture or intellect, but solely on the brute force of inherited status.

Conversely, West Egg glitters with the “new money” of individuals like Gatsby, whose vast fortune can’t purchase the innate lineage or cultural capital required for true acceptance.

This class divide proves impassable. Daisy’s wince of discomfort at Gatsby’s unrestrained West Egg party exposes this deep cultural chasm. The powerful leash of familiar class security and societal expectation inevitably pulls Daisy back to Tom, away from Gatsby’s passionate but unstable dream. Fitzgerald reveals how, in this stratified society, birthright remains paramount, nullifying Gatsby’s intensely American self-made journey.

The desolate Valley of Ashes, a grim industrial wasteland choked by smoke and poverty, presides over the narrative like a guilty conscience. It embodies the human and environmental costs of the system protecting the glittering Eggs, trapping lives like those of George and Myrtle Wilson in hopeless decay.

The Tyranny of Yesterday: Memory and Obsession

Gatsby’s defining belief explodes in his famous retort, “Can’t repeat the past? Why of course you can!” This reveals the tragic core of his destructive obsession.

He directs his obsessive energy not toward building a future, but toward meticulously reconstructing a single, idealized romantic moment from five years prior. This fervent refusal to accept the irreversible passage of time, Daisy’s marriage, and her and Tom’s daughter fuel his potent delusion. He desperately clings to his romanticized memory, imposing it onto the present.

Nick Carraway perceives that Gatsby “wanted to recover something, some idea of himself perhaps, that had gone into loving Daisy.” This insight reveals that Gatsby’s relentless quest for the past is inextricably linked to reclaiming his sense of identity.

The novel, filtered through Nick’s retrospective viewpoint, emphasizes the subjective power of memory while demonstrating the past’s inescapable grip. The narrative culminates in the resonant final image of humanity struggling against time’s relentless backward current.

Gender, Power, and Limited Horizons

While examining social class and the dream, Fitzgerald dissects the constricted roles imposed upon women in the 1920s. Daisy Buchanan, despite her privilege and allure, primarily exists as an object of male ambition. She’s a prize for Gatsby’s dream, and a possession that reinforces Tom’s entitlement.

Her cynical hope that her daughter might be a “beautiful little fool” reveals a bitter awareness of women’s constricted agency; she understands surface charm holds more currency than intelligence or depth. Her decision to retreat into the safety of Tom’s wealth confirms her dependence on established male power structures.

Jordan Baker represents the era’s seemingly liberated “New Woman”, athletic, independent, mobile. Yet Fitzgerald pairs her freedom with emotional detachment and fundamental dishonesty. This juxtaposition suggests the moral ambiguities inherent in navigating newfound independence within a persistently patriarchal society.

Myrtle Wilson possesses a desperate, raw vitality that vividly contrasts with the languid ennui of the women in the Eggs. Yearning to escape the stifling Valley of Ashes, she leverages her sensuality to pursue class mobility through her affair with Tom.

This dangerous path, however, leads only to Tom’s objectification and terminates in her violent death. Her fate illustrates the lethal dangers facing women, especially those from lower classes, who dare to defy the era’s rigid social and gender structures.

Collisions and Consequences: Accidents and Indifference

The novel’s themes — carelessness, class conflict, illusion, and obsession — converge violently in the deaths of Myrtle Wilson and Jay Gatsby.

Earlier, reckless instances foresaw these deaths. The car crash involving Owl Eyes after Gatsby’s party (Chapter 3) and Jordan Baker’s flippant remark about careless driving (“It takes two to make an accident,” Chapter 3) foreshadow the story’s deadly turn.

Myrtle’s demise under the wheels of Gatsby’s yellow car, driven by Daisy, stems directly from the tangled affairs and raw emotions ignited at the Plaza. Dying nameless in the Valley of Ashes, she becomes a brutal casualty of the wealthy’s reckless games and Nick’s passive facilitation.

Gatsby’s subsequent murder by George Wilson marks the definitive shattering of his American Dream. Killed while waiting for a call embodying his persistent illusion, Gatsby dies alone in his pool, a symbol of opulence ironically unused until his final day.

These deaths crystallize Fitzgerald’s piercing critique: in this morally vacant landscape, chasing a corrupted dream breeds destruction. The truly “careless people,” Tom and Daisy, retreat unscathed behind the bulwark of their immense wealth, leaving others like Nick and the reader to grapple with the fatal fallout and their complicity.

Fitzgerald’s Artistry: Crafting the Critique

Choosing Nick Carraway as a first-person, limited narrator creates intimacy while embedding layers of subjectivity. Fitzgerald masterfully compels readers to question Nick’s reliability and interpret events through his evolving judgments, deepening the exploration of perception and arguably making the reader complicit in the initial romantic view of Gatsby.

The novel’s renowned lyrical prose brings the era to life, alive with sensory detail, capturing the parties’ “blue gardens” and “yellow cocktail music” alongside the Valley’s “powdery air.” This distinctive style evokes the seductive glamour of the Jazz Age while revealing its inherent fragility.

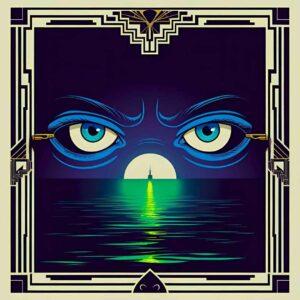

Fitzgerald weaves potent symbols seamlessly into the narrative fabric. The distant green light embodies Gatsby’s hope for the unattainable past. The watchful Eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg brood over the moral wasteland. He skillfully employs structural contrasts and dramatic irony to expose social hypocrisies and amplify the sense of impending tragedy.

The Fading Echo of the Dream

The Great Gatsby delivers Fitzgerald’s haunting diagnosis of the American soul, revealing deep fissures in its most cherished myth.

Jay Gatsby’s magnificent capacity for hope, tragically channeled into recreating an idealized past, shatters against the unyielding social class barriers and the irreversible march of time. His story forms a powerful indictment of an American Dream distorted by materialism, illusion, and the moral carelessness bred by excess wealth.

Through Nick Carraway’s disillusioned voice and Fitzgerald’s luminous prose, the novel transcends its Jazz Age setting. It remains a vital elegy for lost potential and unattainable desires, leaving us to contemplate the enduring power of the past and the meaning of our relentless striving, like “boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

To explore the novel’s powerful language further, delve into our comprehensive collection of The Great Gatsby quotes.

A Note on Page Numbers & Edition:

We carefully sourced textual references for this analysis from The Great Gatsby, Scribner 2020 Paperback edition (Publication Date: September 1, 2020), ISBN-13: 978-1982149482. Just as Gatsby’s carefully constructed identity concealed the simpler truths of James Gatz, page numbers for specific events can differ across various printings. Always double-check against your copy to ensure accuracy for essays or citations.