Is walking merely about burning calories, or could this simple daily activity unlock surprising benefits for your health and well-being?

While weight management often motivates people to start walking, its impact goes far deeper. We’re exposed to health challenges year-round, but strengthening our body’s systems through consistent activity like walking can make a significant difference.

This article explores 30 science-backed benefits of walking every day, from improving circulation and mood to strengthening bones and boosting cognitive function. Discover how incorporating regular walks can be one of the healthiest choices you make.

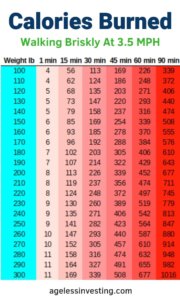

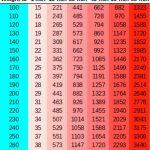

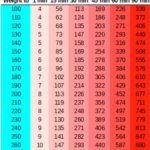

Walking to Lose Weight Chart Lbs: Calories Per Minute

30 Benefits of Walking Every Day

Beyond weight loss, walking offers a wealth of advantages for your physical and mental health:

1. Improves Circulation

Walking increases blood flow, delivering oxygen and nutrients throughout your body more efficiently while removing waste. Good circulation is vital, as poor circulation (often indicated by high blood pressure or peripheral artery disease (PAD)) means arteries are narrowed, potentially causing pain or numbness in extremities (Ref. 1). Walking, as aerobic exercise, strengthens the heart, improves artery flexibility, lowers resting blood pressure, and can even increase red blood cell count (Ref. 2, 3). If walking causes leg pain (claudication), rest and gradually increase distance/duration as circulation improves.

2. Promotes Weight Loss

Walking helps regulate body weight by burning calories, preserving lean muscle, and reducing harmful abdominal (visceral) fat (Ref. 4, 6, 9). While your body stores excess calories as fat, physical activity burns them off (Ref. 7, 8). Walking roughly 1 mile burns about 100 calories (Ref. 10). Though running burns slightly more per mile (Ref. 8), walking is easier to sustain daily and gentler on joints.

3. Burns Harmful Belly Fat

Visceral fat surrounding internal organs increases risks for type 2 diabetes and heart disease (Ref. 12, 13). Regular aerobic exercise like walking is highly effective at reducing this dangerous fat (Ref. 14, 15). Studies show consistent walking significantly reduces waist circumference and body fat percentage (Ref. 16).

4. Builds and Preserves Muscle

Walking tones leg, abdominal, and (if swinging arms) arm muscles. Crucially, it helps preserve lean muscle mass, especially during weight loss. Muscle is more metabolically active than fat, meaning preserving it helps maintain your metabolic rate and keep weight off long-term (Ref. 17, 18, 19, 20, 21). It also helps prevent age-related muscle loss.

5. Lowers Fasting Blood Sugar

Walking, particularly after meals, helps lower blood sugar levels by allowing muscles to use glucose for energy, reducing the burden on insulin and potentially preventing insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (Ref. 22, 23). Studies show post-meal walks are highly effective (Ref. 25). Lowering high fasting blood sugar improves energy utilization and reduces fat storage (Ref. 26). Aiming for walks after dinner can be particularly beneficial.

6. Boosts Your Mood

Walking and other aerobic exercises are proven mood enhancers, reducing anxiety and depression symptoms (Ref. 27, 28). Exercise releases endorphins, which have pain-lowering and mood-lifting effects similar to a “runner’s high” (Ref. 29). It also increases body temperature, improves brain circulation, positively impacts stress response hormones, and provides a mental distraction (Ref. 27). Because walking is enjoyable and not overly strenuous, it’s easier to maintain consistently, reinforcing positive feelings (Ref. 30, 31, 32).

7. Helps Keep Weight Off (Long-Term Maintenance)

Maintaining weight loss is challenging (Ref. 33), but regular exercise like walking is a key predictor of long-term success (Ref. 34). It helps balance energy expenditure and preserves metabolism-boosting muscle mass. Aiming for 200-300 minutes of walking per week is often recommended for weight maintenance or continued loss (Ref. 35, 36, 37).

8. Strengthens Bones

Walking is a weight-bearing exercise that stimulates bones to become denser and stronger, helping to prevent osteoporosis and reduce fracture risk, especially as we age.

9. Improves Sleep

Regular physical activity, including walking (especially if done earlier in the day), can help regulate sleep cycles, making it easier to fall asleep and improving overall sleep quality.

10. Supports Your Joints

Unlike high-impact exercise, walking is gentle on joints. It helps lubricate joints (like knees and hips) and strengthens the muscles surrounding them, reducing stiffness and pain associated with conditions like arthritis.

11. Deepens Your Breathing

Walking increases your respiratory rate, exercising your lungs and improving their capacity to take in oxygen efficiently.

12. Enhances Memory and Cognitive Function

Regular walking boosts blood flow to the brain, which has been linked to improved memory, sharper focus, and better overall cognitive performance.

13. Slows Mental Decline

Studies suggest that physically active individuals, including regular walkers, experience slower rates of age-related cognitive decline and maintain better mental acuity later in life.

14. Helps Prevent Alzheimer’s Disease

Research indicates a link between regular physical activity like walking and a reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia, possibly due to improved brain circulation and reduced inflammation.

15. Keeps You Physically Active (Foundation)

Walking is an accessible foundation for an active lifestyle. It requires no special equipment and can be easily integrated into daily routines, making it easier to meet overall physical activity goals.

16. Improves Balance and Coordination

Walking helps maintain and improve balance and coordination, which is crucial for preventing falls, especially for older adults.

17. Inspires Creativity

Many find that walking, especially outdoors, helps clear the mind and sparks creative thinking and problem-solving.

18. May Relieve Allergies

While intense outdoor exercise might trigger allergies for some, moderate walking can sometimes help by improving circulation and potentially reducing inflammatory responses over time.

19. Saves Money

Walking is free! It requires no gym memberships or expensive equipment, making it a highly cost-effective way to improve health.

20. Lengthens Telomeres

Some research suggests that regular physical activity, including walking, may be associated with longer telomeres – protective caps on the ends of chromosomes linked to cellular aging and longevity. Learn more about how to potentially support telomeres.

21. Helps With Pain Relief

Walking can increase blood flow and release endorphins, which can help alleviate certain types of chronic pain, such as lower back pain or pain from arthritis, by strengthening supporting muscles and improving flexibility.

22. Improves Eyesight

While not a direct cure, walking helps lower blood pressure and manage conditions like diabetes, both of which can negatively impact eye health and contribute to vision problems like glaucoma or retinopathy.

23. Increases Social Time

Walking with friends, family, or neighbours provides an excellent opportunity for social interaction, which is crucial for mental well-being.

24. Improves Digestion

Walking, especially after meals, can aid digestion by stimulating the muscles in the gastrointestinal tract, helping to move food through the system more efficiently and potentially reducing bloating or constipation.

25. Motivates More Healthy Choices

Starting a regular walking habit often creates positive momentum, encouraging individuals to adopt other healthy behaviours like eating better or managing stress more effectively.

26. Boosts Immune Function

Moderate, regular exercise like walking enhances immune cell circulation and function, potentially reducing the frequency and severity of infections like the common cold.

27. Reduces Food Cravings

Some studies suggest that a brisk walk can help reduce cravings for sugary snacks, possibly by altering brain chemistry or providing a distraction.

28. Helps Prevent Varicose Veins

Walking strengthens the circulatory system and leg muscles, which helps support healthy vein function and can reduce the risk or severity of varicose veins.

29. Lowers Risk of Certain Diseases

Beyond heart disease and diabetes, regular walking is associated with a lower risk of certain cancers, stroke, and other chronic conditions.

30. Gives You Fresh Air

Walking outdoors provides exposure to fresh air and potentially sunlight (for Vitamin D production), which can improve mood and overall well-being compared to staying indoors.

Walking Action Plan & Common Questions

Can I Lose Weight By Walking 30 Minutes A Day?

Walking 30 minutes daily is excellent for maintaining health and preventing weight *gain*. However, for significant weight *loss*, aiming for closer to 60 minutes daily (or 200-300+ minutes per week) is generally more effective (Ref. 35, 36).

How Long or Far Should You Walk Every Day?

Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity walking per week (about 2.5 hours), which translates to roughly 20-30 minutes most days or about 1 mile daily. For more significant health benefits or weight loss, aim higher (Ref. 35).

How Long Do You Need To Walk To Start Burning Fat?

Your body primarily uses stored carbohydrates (glycogen) for fuel during the first 20-30 minutes of moderate exercise. After that, it increasingly relies on burning fat stores. Therefore, longer continuous walks (over 30 minutes) are generally better for fat burning than several shorter bursts.

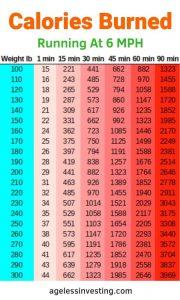

Walking vs. Running for Fat Loss?

Running burns more calories per minute, but walking and running burn roughly the same calories *per mile*. Walking allows for longer durations and is lower impact. Faster walking burns calories quicker and gets you into the fat-burning zone sooner. A mix can be effective.

Simple Walking Action Plan

- Aim for a short walk (10-15 min) after meals, especially dinner, to manage blood sugar.

- Schedule one longer walk (30-60 min) most days.

- If time-crunched, break walks into 10-minute chunks.

- Gradually increase total weekly walking time towards 150-300 minutes.

- Increase intensity sometimes by walking faster, uphill, or using stairs.

- Consider tracking steps (aiming for 7,000-10,000+ daily).

- Listen to your body and rest when needed.

Explore more on optimizing heart health: What is A Good Resting Heart Rate For My Age?

Conclusion: Take the First Step

You already knew walking was good for you, but perhaps seeing these 30 distinct benefits provides fresh motivation. Walking is an accessible, powerful tool for improving nearly every aspect of your physical and mental health, with weight management being just one piece of the puzzle.

Will you take advantage of this simple yet profound activity today?

Related Posts

Sources Cited

- FamilyDoctor.org. (Date Accessed). Peripheral Arterial Disease and Claudication. https://familydoctor.org/condition/peripheral-arterial-disease-and-claudication/

- WebMD Slideshow. (Date Accessed). Hypertension Overview. https://www.webmd.com/hypertension-high-blood-pressure/ss/slideshow-hypertension-overview

- myDr. (Date Accessed). Aerobic exercise – the health benefits. https://www.mydr.com.au/sports-fitness/aerobic-exercise-the-health-benefits

- Hill, J. O., Wyatt, H. R., & Peters, J. C. (2012). Energy Balance and Obesity. *Circulation*, 126(1), 126–132. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2931400/ (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Verywell Fit. (Date Accessed). What Is a Calorie and Why Should I Care?. https://www.verywellfit.com/what-is-a-calorie-and-why-should-i-care-3496238

- Swinburn, B. A., Sacks, G., & Ravussin, E. (2009). Increased food energy supply is more than sufficient to explain the US epidemic of obesity. *The American journal of clinical nutrition*, 90(6), 1453–1456. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28214525 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Schoeller, D. A. (1998). Balancing energy expenditure and body weight. *The American journal of clinical nutrition*, 68(4 Suppl), 956S–961S. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9181668/ (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Wilkin, L. D., Cheryl, A., & Haddock, B. L. (2012). Energy expenditure comparison between walking and running in average fitness individuals. *Journal of strength and conditioning research*, 26(4), 1039–1044. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22446673

- Warburton, D. E., Nicol, C. W., & Bredin, S. S. (2006). Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. *CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne*, 174(6), 801–809. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18562968 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Hall, C., Figueroa, A., Fernhall, B., & Kanaley, J. A. (2004). Energy expenditure of walking and running: comparison with prediction equations. *Medicine and science in sports and exercise*, 36(12), 2128–2134. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20613650 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Compendium of Physical Activities. (Date Accessed). Walking Activity Category. https://sites.google.com/site/compendiumofphysicalactivities/Activity-Categories/walking

- Medical News Today. (Date Accessed). What is visceral fat?. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/320929.php

- Fox, C. S., Massaro, J. M., Hoffmann, U., et al. (2008). Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. *Circulation*, 118(1), 39–48. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18220642 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Slentz, C. A., Aiken, L. B., Houmard, J. A., et al. (2011). Inactivity, exercise training and visceral fat. STRRIDE: a randomized, controlled study of exercise intensity and amount. *Journal of applied physiology*, 111(6), 1518–1525. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21951360 (*Note: Link may require access*)

- Irving, B. A., Davis, C. K., Brock, D. W., et al. (2008). Effect of exercise training intensity on abdominal visceral fat and body composition. *Medicine and science in sports and exercise*, 40(11), 1863–1872. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17637702 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Hong, H. R., Jeong, J. O., Kong, J. Y., et al. (2014). Effect of walking exercise on abdominal fat, insulin resistance and serum cytokines in obese women. *Journal of exercise nutrition & biochemistry*, 18(3), 277–285. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25566464

- Konopka, A. R., & Harber, M. P. (2014). Skeletal muscle hypertrophy after aerobic exercise training. *Exercise and sport sciences reviews*, 42(2), 53–61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20591106 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Willis, L. H., Slentz, C. A., Bateman, L. A., et al. (2012). Effects of aerobic and/or resistance training on body mass and fat mass in overweight or obese adults. *Journal of applied physiology*, 113(12), 1831–1837. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28507015 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Ballor, D. L., Katch, V. L., Becque, M. D., & Marks, C. R. (1988). Resistance weight training during caloric restriction enhances lean body weight maintenance. *The American journal of clinical nutrition*, 47(1), 19–25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7713045/ (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Stiegler, P., & Cunliffe, A. (2006). The role of diet and exercise for the maintenance of fat-free mass and resting metabolic rate during weight loss. *Sports medicine*, 36(3), 239–262. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19276190 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Weinheimer, E. M., Sands, L. P., & Campbell, W. W. (2010). A systematic review of the separate and combined effects of energy restriction and exercise on fat-free mass in middle-aged and older adults: implications for sarcopenic obesity. *Nutrition reviews*, 68(7), 375–388. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24457527 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- NIDDK. (Date Accessed). What is Diabetes?. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/what-is-diabetes

- NIDDK. (Date Accessed). Preventing Diabetes Problems. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/preventing-problems

- Williams, P. T., & Thompson, P. D. (2013). Walking versus running for hypertension, cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus risk reduction. *Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology*, 33(5), 1085–1091. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/atvbaha.112.300878

- DiPietro, L., Gribok, A., Stevens, M. S., Hamm, L. F., & Rumpler, W. (2013). Three 15-min bouts of moderate postmeal walking significantly improves 24-h glycemic control in older people at risk for impaired glucose tolerance. *Diabetes care*, 36(10), 3262–3268. http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/early/2013/06/03/dc13-0084

- UCSF SugarScience. (Date Accessed). Sugar Metabolism. http://sugarscience.ucsf.edu/sugar-metabolism.html#.XA8NZWhKi00

- Paluska, S. A., & Schwenk, T. L. (2000). Physical activity and mental health: current concepts. *Sports medicine*, 29(3), 167–180. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15518309/ (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Salmon, P. (2001). Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory. *Clinical psychology review*, 21(1), 33–61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9973590 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- WebMD. (Date Accessed). Exercise and Depression. https://www.webmd.com/depression/guide/exercise-depression#1

- Lawton, B. A., Rose, S. B., Elley, C. R., Dowell, A. C., Fenton, A., & Moyes, S. A. (2008). Exercise on prescription for women aged 40-74 recruited through primary care: two year randomised controlled trial. *BMJ*, 337, a2509. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16901889/ (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Rhodes, R. E., Fiala, B., & Conner, M. (2019). A review and meta-analysis of affective judgments and physical activity behavior. *Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine*, 53(7), 640–652. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25921307 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Kwan, B. M., & Bryan, A. D. (2010). Affective response to exercise as a component of exercise motivation: attitudes, norms, self-efficacy, and temporal stability of intentions. *Psychology of sport and exercise*, 11(1), 71–79. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4333108/ (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Wing, R. R., & Phelan, S. (2005). Long-term weight loss maintenance. *The American journal of clinical nutrition*, 82(1 Suppl), 222S–225S. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16002825

- Jakicic, J. M., Marcus, B. H., Gallagher, K. I., Napolitano, M., & Lang, W. (2003). Effect of exercise duration and intensity on weight loss in overweight, sedentary women: a randomized trial. *JAMA*, 290(10), 1323–1330. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15561636 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- Donnelly, J. E., Blair, S. N., Jakicic, J. M., Manore, M. M., Rankin, J. W., & Smith, B. K. (2009). American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. *Medicine and science in sports and exercise*, 41(2), 459–471. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26574810 (*Note: Link title doesn’t match abstract – verify relevance*)

- Jakicic, J. M., Winters, C., Lang, W., & Wing, R. R. (1999). Effects of intermittent exercise and use of home exercise equipment on adherence, weight loss, and fitness in overweight women: a randomized trial. *JAMA*, 282(16), 1554–1560. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19127177 (*Note: Link abstract differs*)

- McGuire, M. T., Wing, R. R., Klem, M. L., Lang, W., & Hill, J. O. (1999). What predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers?. *Journal of consulting and clinical psychology*, 67(2), 177–185. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10546695

An impressive content enumerating the different benefits we can get from walking. When my office was just a few meters away from my home, I walk everyday ti and from the office. I should say, that was very helpful. However, nowadays, my office is 60 kilometers away from home and need to use public transport everyday. I also lost the opportunity to walk. Perhaps i could devote more time in walking even on a weekend. Thank you for sharing such a helpful piece.

Thank you, Sharon! Researching for this article helped me realize that walking every day is one of the simplest and most powerful things you can do for your health. That’s unfortunate about your lost walking to and from work opportunity. Evenings and weekends are great as well. Good luck with your career.

Impressive post! Walking is one of my favorite exercise routines. Just wish there’s more time to do that.

Thank you, Mary! It’s even harder to find time to walk in the winter. Never underestimate the benefit if even a quick walk. I try a short walk almost every day at the gym and it has helped me lift more weight and run faster month after month.

I started walking on my lunch time again recently. I joined the gym at work. It is a great stress reliever in the daytime and I have been forcing myself, even when I don’t feel like it, and am glad I did it when done!

Thank you! Yes, walking makes everything easier with a clearer mind and more energy. Enjoy your walks.

Great blog, good read and informative.

Thank you, Sid!

Walking is really amazing since it will provide you a great weight loss.

Love this! Thank you for sharing!

Oooooh so useful! Thanks 🙂

Your welcome, Sophie!!!

Walking and diet does work. I started May 3rd 2021 on a low carb low sugar diet. No bread but one slice a week. Also only drink one soda a week that’s diet. Over the last three months I lost 29 pounds. I walk about 3 miles a day and keep the diet going. It’s been a wild ride with amazing results.

Thank you, David! Congrats on your progress!

What a great and inspiring article. In the past I had a regular walking program going. And you are right when you say it makes everything better — weight, energy, emotions, and clear thinking. Circulation, right? I will find a way to get my daily walk back. Thanks for the nudge.

Thank you, Grammye!!! Yes, and it’s free.