The Great Gatsby’s theme of illusion vs. reality is a dual-layered deception that ensnares the characters and the reader alike.

The first layer is Jay Gatsby’s conscious performance of a fabricated identity. The second, more critical layer is the romanticized myth that our narrator, Nick Carraway, crafts for us.

Our analysis argues that Fitzgerald’s true genius lies in this dual structure. To understand the novel’s tragedy, we must first deconstruct Gatsby’s elaborate stage play, then expose Nick’s role as an unreliable mythmaker, and finally examine the recurring motif of sight and blindness to see who, if anyone, ever perceives the truth.

Please note: This analysis discusses the plot of the entire novel, including its conclusion.

The Great Performer: Gatsby’s Construction of an American Illusion

Jay Gatsby is the ultimate self-made man, but his creation isn’t a business or an empire; it’s himself. His entire life is a meticulously staged theatrical production designed to project an image of effortless wealth and inherited status. In this section, we’ll analyze the key elements of Gatsby’s performance, from his fabricated past to his idealized vision of the future, revealing the hollow core beneath the glittering facade.

The Fabricated Past: Inventing “Jay Gatsby”

Gatsby’s grand illusion begins with the complete erasure of his true identity. The man named Jay Gatsby is an invention; the reality is James Gatz, a poor farm boy from North Dakota.

He presents Nick with a carefully edited story of being the “son of some wealthy people in the Middle West” who was “educated at Oxford,” a claim so rehearsed that it chokes him [Chapter 4, Page 65]. This fabrication isn’t merely a lie; it’s a strategic necessity.

He understands that to win Daisy, a product of the “old money” elite, he needs a past that is worthy of her. His real education in the ways of the wealthy didn’t come from a university; it came at the side of a boorish millionaire on a yacht.

This real-world education in the ways of the wealthy is a fascinating story in itself, a topic we explore in our full character analysis of Dan Cody.

The Theatrical Present: The Mansion, the Parties, and the Uncut Books

If Gatsby’s past is a rewritten script, his present is an elaborate stage production. His mansion isn’t a home but a set, a “factual imitation of some Hôtel de Ville in Normandy” [Chapter 1, Page 5]. His legendary parties are not celebrations. They are performances, a “spectroscopic gayety” designed to generate a myth so large it might capture Daisy’s attention [Chapter 3, Page 49].

The most telling detail of this stagecraft is found in the library. There, a drunken guest marvels that the books are real, not “a nice durable cardboard.” But in his astonishment, he reveals the secret: “‘Knew when to stop, too—didn’t cut the pages'” [Chapter 3, Page 46].

Gatsby has acquired the perfect props for an intellectual life, but he hasn’t performed the act of reading. This crucial insight is provided by Owl Eyes, the one guest who sees the stagecraft, and you can read more about his symbolic role in our dedicated analysis.

The Idealized Future: Daisy as an Unattainable Illusion

The object of this entire performance, Daisy Buchanan, is an illusion in Gatsby’s mind. He loves an idealized memory, not the real, flawed woman.

Nick perceives this with stunning clarity, noting that after their reunion, Daisy must have “tumbled short of his dreams—not through her own fault, but because of the colossal vitality of his illusion. It had gone beyond her, beyond everything” [Chapter 5, Page 95].

No real person could ever live up to the fantasy Gatsby has stored “in his ghostly heart.” The one piece of undeniable reality shatters the dream he can’t ignore: Daisy’s daughter. This truth is made painfully real by the appearance of Pammy, the child who serves as the dream’s ultimate rebuttal, a topic we explore in our analysis of what Pammy Buchanan symbolizes.

Gatsby as the Original Influencer: A Modern Performance

Gatsby’s elaborate performance is a chilling prophecy of our modern digital age. He’s, in essence, the original social media influencer. Lacking a verified “blue check” of old money, he instead curates a public feed of spectacular content, his parties, his mansion, his hydroplane, all designed to project an image of success and attract a specific follower: Daisy.

His entire life is an exercise in “personal branding,” meticulously crafting an illusion of effortless perfection to mask the messy reality of his origins. In an era before Instagram, Gatsby understood the core principle of performative identity: if you can make the illusion compelling enough, the reality almost ceases to matter.

The Unreliable Mythmaker: How Nick Carraway Creates the Legend

While Gatsby performs for the characters, Nick Carraway performs for us. Far from a neutral observer, Nick is an active and unreliable mythmaker who is seduced by Gatsby’s dream and crafts a romantic legend for the reader. In this section, we’ll analyze how Nick’s narration is itself a layer of illusion that we must see through to grasp the novel’s harsher realities.

“Reserving Judgments”: The Narrator’s First Illusion

Nick Carraway’s first act as narrator is to create an illusion of his objectivity. He opens his story with the advice his father gave him: to “reserve all judgments” [Chapter 1, Page 1]. This statement is a deliberate narrative strategy designed to win our trust, positioning him as a fair and impartial guide.

Yet, he immediately shatters this illusion in the very next paragraph. After boasting of his tolerance, he declares: “Only Gatsby, the man who gives his name to this book, was exempt from my reaction” [Chapter 1, Page 2]. This is not a minor exception; it represents a fundamental acknowledgment of bias.

Before the story even begins, Nick acknowledges that he has positioned Gatsby beyond the bounds of typical judgment. This signals to the reader that the narrative we are about to hear is not an objective account but rather a subjective and ultimately romanticized defense of Gatsby.

The Romantic Lens: Narrating the “Gorgeous” Dream

Throughout the novel, Nick consistently uses a romantic lens to build the Gatsby myth. His word choices aren’t those of a detached observer but of a captivated storyteller.

He describes Gatsby as having an “extraordinary gift for hope, a romantic readiness such as I have never found in any other person” [Chapter 1, Page 2]. He sees not just a man with a flawed obsession; he also perceives something “gorgeous” and unique.

This romanticized language filters every event. Gatsby’s parties are more than just drunken spectacles; they’re enchanted gatherings under the stars. His smile is beyond just charming; it’s one of those “rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it” [Chapter 3, Page 48].

By consistently applying this elevated, almost mythic language to Gatsby, while using cynical and critical language for characters like Tom and Daisy, Nick actively shapes our perception. He’s not just telling us a story; he’s convincing us to see Gatsby as he does: a tragic hero in a world full of careless people.

The Final Mythmaking: “You’re Worth the Whole Damn Bunch”

Nick’s final judgment of Gatsby is the ultimate act of mythmaking, where he consciously erases his subject’s significant flaws to elevate him to legendary status.

His last words to Gatsby, shouted across the lawn, are a passionate defense, not an objective assessment: “They’re a rotten crowd… You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.” [Chapter 8, Page 154]. In this moment, Nick makes a deliberate moral choice. He chooses the romantic illusion of Gatsby, the man who believed in the “green light,” over the foul reality of the Buchanans’ destructive carelessness.

It’s the final, cementing act in his narrative performance, a moment where he completes the legend he’s been crafting all along. To understand the full complexity of our narrator’s motivations, you can explore our complete character analysis of Nick Carraway.

The Eyes of the Novel: A Thematic Analysis of Sight and Blindness

Fitzgerald weaves a powerful motif of eyes and vision throughout the novel to explore the theme of illusion and reality. From vacant billboards to perceptive party guests, the characters who can truly “see” are few and far between. In this section, we’ll contrast the novel’s key “eyes” to reveal who’s blind to reality and who can see through the facade.

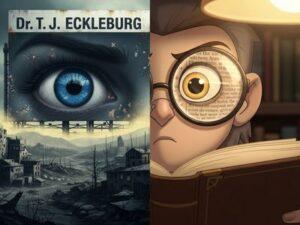

The Eyes of Eckleburg: The Gaze of Indifferent Reality

The most prominent eyes in the novel belong to Doctor T. J. Eckleburg, staring from a faded billboard over the Valley of Ashes. They are left over from a defunct business, not the eyes of a watchful God.

Nick describes them as “blue and gigantic,” but their gaze is “paintless” and vacant [Chapter 2, Pages 23-24]. They represent a harsh, unseeing, and commercialized reality. They see the squalor of the valley and the frantic comings and goings of the characters. But they offer no judgment, no comfort, and no intervention.

When George Wilson later mistakes them for the eyes of God, it’s a moment of heartbreaking irony. He projects a need for moral order onto a symbol of commercial indifference, highlighting a world where true vision has been abandoned, leaving only the hollow gaze of advertising to witness the tragedy.

The Eyes of Owl Eyes: The Gaze of Perceptive Detachment

In direct contrast to Eckleburg’s unseeing eyes are those of the man Nick calls “Owl Eyes.” He’s the only character who actively investigates Gatsby’s illusion. While drunk in the library, he’s the one who bothers to check if the books are real, marveling at the theatricality of the facade: “This fella’s a regular Belasco” [Chapter 3, Page 46].

His drunken, blurred vision is a perfect irony, as his spectacles grant him a sharper perception of the truth than any other character possesses. He sees that Gatsby’s world is a masterful stage production. Yet, his insight is that of a detached observer, not a participant.

His final appearance, as one of the few mourners at Gatsby’s funeral, is telling. Sober and clear-eyed in the rain, he’s the one who sees the final, grim reality of Gatsby’s isolation, offering the closing verdict: “The poor son-of-a-bitch” [Chapter 9, Page 175].

Gatsby’s Blind Gaze: Focused Only on the Past

Jay Gatsby, the novel’s central illusionist, is metaphorically blind. His vision is completely consumed by a single, distant point of light that exists only in his memory. From the first moment Nick sees him, Gatsby is “stretching out his arms toward the dark water,” reaching for a “single green light, minute and far away” [Chapter 1, Page 21].

This singular focus on the past blinds him to the present reality. He can’t see Daisy for the flawed, indecisive person she truly is. He can’t see Tom as the insurmountable and brutal obstacle he represents. He can’t see the moral decay that his criminal enterprise entails.

Gatsby’s gaze is fixed so intently on the illusion of a perfect, repeatable past that he’s completely blind to the destructive reality unfolding all around him.

When the Curtain Falls on the Dream

The theme of illusion versus reality in The Great Gatsby is a masterfully constructed deception on two fronts.

The first illusion, Gatsby’s grand performance of wealth and status, is a spectacular failure of substance. It’s a theatrical production that is ultimately dismantled by the harsh, unforgiving reality of the class system and the past he can’t erase.

But the second, more enduring illusion is Nick Carraway’s narrative performance. His romantic mythmaking succeeds where Gatsby’s fails, crafting a legend so compelling that it seduces us, the readers, into seeing a “gorgeous” dream even as we witness its foul and dusty collapse.

Fitzgerald’s ultimate genius is this implication of the reader. We’re forced to confront our preference for a beautifully told lie over an ugly truth.

The novel’s power endures not just as a critique of a bygone era, but as a timeless exploration of the human tension between the lives we live and the more compelling stories we choose to tell about them. In the end, the curtain falls not just on Gatsby’s dream, but on our willingness to believe in it.

For a broader look at how this theme intersects with the novel’s other critical ideas, you can explore our complete analysis of The Great Gatsby.

A Note on Page Numbers & Edition:

Just as Nick Carraway’s narration filters our view of reality, page numbers can shift between different printings of the novel. We meticulously sourced textual references for this analysis from The Great Gatsby: The Only Authorized Edition, Scribner, November 17, 2020, ISBN-13: 978-1982149482. Always double-check against your copy to ensure accuracy for essays or citations.