The Great Gatsby‘s Social Class Theme is one of the novel’s most unbreachable walls, a rigid hierarchy defined not just by wealth, but by a language of unspoken rules and inherited tastes.

Our analysis argues that Fitzgerald’s masterpiece is a tragedy of performance and enforcement. We explore how Jay Gatsby, despite his wealth, is an outsider who can only imitate the language of the elite, while Tom Buchanan acts as its native speaker and brutal gatekeeper, ensuring the American Dream remains a beautiful, unattainable illusion.

Please note: This analysis discusses the plot of the entire novel, including its conclusion.

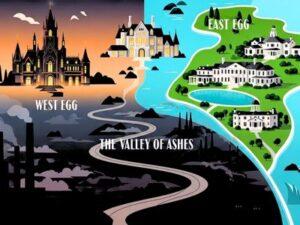

The Geography of Class: East Egg, West Egg, and the Valley of Ashes

In The Great Gatsby, where you live is who you are. F. Scott Fitzgerald masterfully uses the geography of Long Island and New York City to create a physical map of the American class system.

In this section, we’ll explore the distinct moral and social worlds of East Egg, West Egg, and the Valley of Ashes, analyzing how these settings are not mere backdrops but active forces that define their inhabitants’ possibilities and seal their fates.

The novel immediately establishes its social hierarchy through setting. East Egg is the fortress of inherited power, a world of “white palaces” populated by families like the Buchanans. Their “cheerful red-and-white Georgian Colonial mansion” does not simply sit on the water; it asserts its dominance, with a lawn that runs “toward the front door for a quarter of a mile” [Chapter 1, Page 6].

The sensory experience here is one of effortless space and light, of manicured lawns and breezy, sun-filled rooms. This physical ease reflects the inhabitants’ unthinking security, a world so insulated by generations of wealth that it has grown careless and morally vacant.

West Egg contrasts as the stage for performative wealth. Nick Carraway, our narrator, immediately understands the distinction, labeling his new home as “the less fashionable of the two” [Chapter 1, Page 5]. While the wealth in West Egg is immense, it’s new, anxious, and lacks the inherited cultural codes of the East.

Gatsby’s mansion, a “colossal affair,” is a perfect example. It’s a “factual imitation of some Hôtel de Ville in Normandy,” a conscious and spectacular copy of European aristocracy [Chapter 1, Page 5]. The sensory details here are not of serene luxury, but of spectacle: the “gaudy” colors of the parties, the loud “yellow cocktail music,” and a “raw vigor” that Daisy finds so appalling [Chapter 6, Page 107]. West Egg is a world that tries desperately to be impressive, and in doing so, reveals its insecurity.

Between these two worlds of wealth lies their grim consequence: the Valley of Ashes. Fitzgerald’s description of this industrial wasteland is one of the most powerful indictments of the class system. This is “a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens” [Chapter 2, Page 23].

The sensory experience is oppressive and suffocating. The inhabitants are “ash-gray men” who “move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air.” The Valley is not merely a poor area; it’s the dumping ground for the industrial and moral refuse of the glittering Eggs. It’s a place of entrapment, a physical manifestation of the human cost of the elite’s careless lifestyle, making the American Dream of mobility feel like a cruel joke.

To fully grasp the oppressive atmosphere of this industrial wasteland, you can explore our collection of quotes from the Valley of Ashes, which capture its bleakness in Fitzgerald’s own words.

The Language of Status: Performance and “Cultural Capital”

Beyond geography, social class in the novel is a meticulous and often flawed performance. It’s seen in the clothes characters wear, the phrases they adopt, and the way they carry themselves in a room. In this section, we’ll introduce the concept of “cultural capital” to analyze how characters use, or fail to use, the language of status, revealing that true belonging can’t be purchased.

Gatsby’s Flawed Performance

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu coined the term “cultural capital” to describe the non-financial assets, such as education, taste, and inherited manners, that signal one’s social standing. Jay Gatsby’s tragedy is a perfect illustration of a man who possesses immense economic capital but lacks the cultural capital to make it legitimate.

His entire life is a performance of a class to which he was not born. His repeated use of “old sport,” for instance, is a verbal tic he likely believes conveys the easy camaraderie of the elite. But his stiff, constant repetition marks it as a learned affectation [Chapter 4, Page 67].

Similarly, his “gorgeous” pink suit is a display so flamboyant that it betrays his new-money origins. Tom Buchanan weaponizes this immediately, dismissing Gatsby’s entire identity with a sneer: “An Oxford man! … He wears a pink suit” [Chapter 7, Page 122]. In Tom’s world, actual status is communicated through understated confidence, not loud display.

Even Gatsby’s magnificent library is a facade. Owl Eyes, in a moment of drunken clarity, marvels that the books are real, but notes with surprise that the pages are uncut [Chapter 3, Page 46]. Gatsby has acquired the props of an intellectual life, but he has not performed the act of reading them. His performance is a perfect, hollow shell.

This calculated performance is central to understanding his entire identity. For a more complete portrait of his motivations and ultimate failure, you can delve deeper into our full character analysis of Jay Gatsby.

The Vulgar Imitation of the McKees

If Gatsby’s performance is flawed, the performance of the McKees at Myrtle’s apartment party is a transparent failure. They serve as a foil to Gatsby, representing a lower-middle-class aspiration that is even further removed from the authenticity of the elite.

Mr. McKee attempts to speak the language of the art world, pretentiously naming his photographs “Montauk Point—the Gulls” and “Montauk Point—the Sea,” an effort that falls flat on the brutish Tom [Chapter 2, Page 36].

Mrs. McKee, meanwhile, offers compliments that betray her unfamiliarity with high society, telling Myrtle her dress is “adorable” and gushing that her husband could “make something of it” if he could photograph her in that pose [Chapter 2, Page 35]. Their attempts to perform sophistication are clumsy and transparent, highlighting just how complex the language of class is to learn for those not born into it.

The Transactional Presence of Klipspringer

Ewing Klipspringer, known as “the boarder,” represents the cynical endpoint of a world where social connections are transactional. He’s a class parasite, a man who performs just enough civility to earn his keep in Gatsby’s mansion, enjoying the material benefits without any genuine loyalty. He understands the language of class well enough to know that Gatsby’s world is built on spectacle, and he’s happy to be part of the audience as long as the show continues.

His true nature is revealed in one of the novel’s most damning scenes. After Gatsby’s death, Klipspringer calls Nick not to offer condolences or ask about the funeral, but to inquire about a lost pair of tennis shoes [Chapter 9, Page 169]. This single act exposes the absolute hollowness of the social world Gatsby built. When the money and the parties disappear, so do the “friends,” revealing that the only language Klipspringer truly speaks is that of selfish opportunism.

The Gender of Judgment: How Class Rules Differ for Men and Women

The unspoken language of class is not applied equally. Fitzgerald subtly reveals that men and women are evaluated based on different criteria. In this section, we’ll analyze how male status is tied to the origin and authenticity of their wealth, while female status is judged by their ability to perform their designated role within the class structure.

Men Judged on Origin

In the world of The Great Gatsby, the ultimate measure of a man is not the size of his fortune, but its origin. The central conflict between Tom and Gatsby is a battle over authenticity.

Tom’s power is absolute because his class is inherited; it’s a birthright, as solid and unassailable as his “cruel body” [Chapter 1, Page 7]. He never has to justify his position because it has always been his. Gatsby, on the other hand, is judged relentlessly for the newness of his wealth. His entire identity is suspect because it was created, not inherited.

Tom’s final, victorious blow in the Plaza Hotel does not prove that Gatsby is a bad man, but that he’s a bootlegger [Chapter 7, Page 133]. By exposing the criminal origins of Gatsby’s money, Tom reveals his class “illiteracy” in the most damning way possible, proving he’s not, and never can be, one of them.

Women Judged on Performance

While the men are judged on their origins, the women are judged on their ability to perform their assigned roles within the class structure.

Daisy Buchanan’s immense value in this world is tied to her flawless performance as the “golden girl” of the elite. Her charm, her voice, and even her cynicism are all part of a carefully maintained presentation that makes her the ultimate prize for both Tom’s security and Gatsby’s ambition. Her greatest transgression is not her affair, but her momentary hesitation to perform her role as Tom’s wife, a lapse she quickly corrects by retreating into the safety of his world.

Myrtle Wilson’s tragedy, in contrast, is her failed performance. She tries to play the part of a wealthy man’s sophisticated mistress, but her “impressive hauteur” is transparently affected and seen as vulgar [Chapter 2, Page 31]. She’s judged not for her ambition, but for her clumsy and inauthentic imitation of a class she doesn’t understand, a failure that ultimately places her in the path of the speeding car.

Daisy’s complex role as both a product and a perpetrator of the class system’s rules is central to the novel’s tragedy, a dynamic we explore in our complete character analysis of Daisy Buchanan.

The Gatekeeper: How Tom Buchanan Enforces the Class Boundary

A social order this rigid requires enforcement. While many characters accept the class hierarchy, Tom Buchanan acts as its aggressive and violent gatekeeper. In this section, we’ll analyze how Tom’s primary function in the narrative is to identify, challenge, and expel Gatsby from the elite circle, protecting the purity of his inherited world and ensuring the unbreachable wall of class remains intact.

The Investigation as Social Policing

Tom’s reaction to Gatsby isn’t one of simple romantic jealousy; it’s the immediate, instinctual response of a territorial animal sensing an intruder.

From the moment he learns of Gatsby’s existence, he begins a “small investigation of this fellow,” driven by a need to expose him as a fraud [Chapter 7, Page 129]. He questions Gatsby’s origins, mocks his claims of being an “Oxford man,” and dismisses his parties as a “menagerie.”

This isn’t just personal dislike; it’s an act of social policing. Tom’s goal is to peel back the layers of Gatsby’s carefully constructed performance to reveal the “new money” origins he finds so contemptible. He’s determined to prove that Gatsby, despite his immense wealth, doesn’t belong.

The Confrontation as a Class Tribunal

The sweltering confrontation at the Plaza Hotel functions as a class tribunal, with Tom as the prosecutor and judge. While the conflict is ostensibly over Daisy, Tom’s true weapon is class. He systematically dismantles Gatsby’s identity, not by questioning his love for Daisy, but by attacking the source of his wealth.

When he finally declares, “I found out what your ‘drug-stores’ were… He and this Wolfshiem bought up a lot of side-street drug-stores here and in Chicago and sold grain alcohol over the counter” [Chapter 7, Page 133]. He’s doing more than revealing a crime. He’s branding Gatsby with the indelible stain of “trade” and illegitimacy, proving to Daisy that Gatsby’s fortune is not just new, but dirty.

This is the knockout blow from which Gatsby can’t recover, as it shatters the illusion of aristocratic legitimacy he so desperately needs to win Daisy.

The Final Enforcement: Weaponizing the Lower Class

Tom’s final act as gatekeeper is his most ruthless. After Myrtle’s death, when a distraught George Wilson appears at his door, Tom sees an opportunity to eliminate his rival permanently. He coldly and deliberately directs Wilson toward Gatsby, knowing full well that Gatsby wasn’t Myrtle’s lover in the way Wilson imagines.

He tells Nick later, with chilling self-justification, “He had it coming to him. He ran over Myrtle like you’d run over a dog and never even stopped his car” [Chapter 9, Page 178]. In this moment, Tom uses a member of the lower class as a weapon to destroy the “new money” threat. He restores the social order by ensuring the outsider isn’t just expelled, but annihilated, preserving the unbreachable wall between his world and Gatsby’s.

This aggressive policing of the social order is a defining aspect of his personality. Our complete character analysis of Tom Buchanan unpacks his motivations in greater detail.

The Unbreachable Wall That Doomed the Dream

Fitzgerald’s critique of social class in The Great Gatsby is absolute. Through the symbolic geography of the Eggs and the Ashes, the desperate performance of status, and Tom Buchanan’s brutal enforcement of the boundary, the novel argues that the American class system is an unbreachable wall.

Gatsby’s tragedy isn’t that his dream was flawed, but rather that in a world where lineage outweighs merit, his failure was unavoidable. The novel endures as a powerful warning that the promise of the American Dream remains hollow as long as such rigid social barriers exist.

To hear these class distinctions in the characters’ own words, explore our complete collection of quotes on social class in The Great Gatsby.

A Note on Page Numbers & Edition:

Just as the ‘courtesy bay’ separates the two Eggs, page numbers can create a small but significant gap between different printings of the novel. We meticulously sourced textual references for this analysis from The Great Gatsby: The Only Authorized Edition, Scribner, November 17, 2020, ISBN-13: 978-1982149482. Always double-check against your copy to ensure accuracy for essays or citations.