Chapter 7 forces a devastating confrontation: can Gatsby’s idealized past truly be resurrected, or will the present’s harsh realities irrevocably shatter his American Dream?

Following Chapter 6’s unveiling of Gatsby’s constructed past, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby hurtles into its devastating climax in Chapter 7. This pivotal, longest chapter ignites the summer’s simmering tensions, unleashing catastrophic consequences that irrevocably alter the characters’ lives.

As narrator Nick Carraway is pulled deeper into the emotional vortex, you witness Gatsby’s desperate hope collide with old money’s callous power and time’s irreversible current.

First, a concise summary recaps the chapter’s key events. Our subsequent analysis argues that Fitzgerald masterfully uses these dramatic developments to expose the brutal fallout of Gatsby’s unattainable dream and the elite’s moral bankruptcy, revealing the irreversible shattering of illusions through Nick’s disillusionment.

(For context on Gatsby’s origins and his belief in repeating the past, see the Chapter 6 Summary & Analysis.)

The Great Gatsby Chapter 7 Summary

On the summer’s hottest day, simmering tensions boil over, leading to a fateful confrontation in New York, a tragic accident in the valley of ashes, and the beginning of Gatsby’s ultimate undoing.

Parties Cease, Tensions Simmer

Gatsby abruptly stops throwing lavish weekend parties. Nick learns Gatsby has also fired his entire staff, replacing them with “some people Wolfsheim wanted to do something for”, shady individuals less likely to gossip about Daisy’s now frequent afternoon visits, a clear sign of their deepening affair.

The Weight of Ennui: Daisy’s Search for Distraction

The oppressive heat amplifies an underlying existential boredom, particularly for Daisy. Her plaintive cry, “What’ll we do with ourselves this afternoon… and the day after that, and the next thirty years?” reveals a deep dissatisfaction despite her immense privilege.

It’s a desire for any diversion from the stifling present. Jordan’s characteristically pragmatic retort, “Life starts all over again when it gets crisp in the fall,” highlights a resilience or perhaps a cynical acceptance that Daisy lacks.

Daisy’s subsequent impulsive suggestion to go to the city isn’t just a reaction to Gatsby, but a desperate grasp for any activity to fill the void, ironically setting the stage for the chapter’s tragic confrontations.

Love Unveiled, Confrontation Ignited

The oppressive heat and unspoken tensions make the luncheon strained. Daisy, restless and perhaps seeking an escape from the stifling atmosphere, exclaims to the group, “What’ll we do with ourselves this afternoon… and the day after that, and the next thirty years?” Jordan Baker offers a typically pragmatic response: “Don’t be morbid… Life starts all over again when it gets crisp in the fall.”

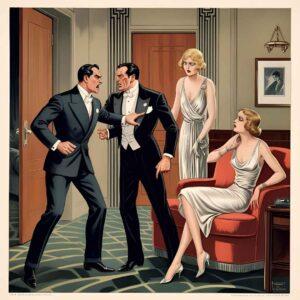

The charged mood intensifies when Daisy, looking directly at Gatsby before everyone, declares, “You always look so cool.” Tom, witnessing this intimate exchange and the undisguised emotion in Daisy’s eyes, definitively realizes the depth of their affair. Reacting to the loaded atmosphere and perhaps Tom’s dawning awareness, Daisy impulsively suggests, “Let’s all go to town!” Tom, now eager for a confrontation, aggressively seizes upon her idea.

Daisy and Jordan go upstairs to prepare for the trip to the city, leaving Nick and Gatsby alone. In this interlude, Gatsby privately tells Nick that Daisy’s voice “is full of money.”

The Car Swap: A Fateful Decision

A tense argument erupts over driving arrangements. Tom asserts his dominance by insisting on driving Gatsby’s conspicuous yellow car, taking Nick and Jordan with him. Gatsby and Daisy follow in Tom’s less remarkable blue coupé, a swap that with deadly consequences.

Wilson’s Garage: Seeds of Tragedy

Tom, at the wheel of Gatsby’s car, stops for gas at George Wilson’s garage in the desolate valley of ashes. Wilson appears physically ill, his face “green.” He reveals to Tom his recent discovery of Myrtle’s infidelity (though he doesn’t know Tom is the other man) and his desperate plan to take her West. During this charged stop, Myrtle, looking from an upstairs window, sees Jordan Baker in the yellow car alongside Tom. She tragically misidentifies Jordan as Daisy, Tom’s wife.

The Plaza Hotel: Dreams Shatter

The group takes a stifling suite at the Plaza Hotel, the oppressive heat mirroring the escalating tension. Tom aggressively confronts Gatsby, mocking his “old sport” affectation and challenging his Oxford claim. Gatsby explains he attended for five months in a post-war army program.

When Tom demands Gatsby’s intentions toward Daisy, Gatsby boldly declares that Daisy loves him and never loved Tom. Tom counters by invoking his shared history with Daisy.

Pressured by Gatsby to renounce her past, Daisy falteringly admits she loved Tom once, but now loves Gatsby. This confession stuns Gatsby.

Tom then plays his trump card, revealing his investigation into Gatsby’s affairs and accusing him of being a bootlegger with illicit criminal connections. Daisy, terrified by these revelations, withdraws completely from Gatsby, her resolve shattered.

Tom, triumphant, contemptuously tells Gatsby to drive Daisy home in his yellow car. Amidst this emotional wreckage, Nick suddenly, poignantly, remembers it’s his 30th birthday.

The “Death Car”: Myrtle’s Violent End

As Nick, Tom, and Jordan drive back towards Long Island, the narrative briefly incorporates the testimony of Michaelis, Wilson’s neighbor. Michaelis recounts that Wilson had locked a distraught Myrtle upstairs.

She eventually escaped and ran into the road, directly into the path of a speeding yellow car coming from New York. The car struck and killed her instantly, pausing only for a moment before disappearing into the dusk.

Aftermath and Deception

Tom, Nick, and Jordan arrive at the chaotic accident scene. Tom, after a brief display of shock over Myrtle’s body, learns from a policeman that witnesses identified the “death car” as yellow. He quickly manipulates a distraught George Wilson, implying the car wasn’t his and that Gatsby was likely the driver, thereby deflecting all suspicion from himself.

Gatsby’s Vigil, Nick’s Disgust

Later that night, Nick discovers Gatsby hiding in the shrubbery outside the Buchanans’ house. Gatsby admits Daisy was driving the car that struck Myrtle, but insists he will take the blame. He waits, he claims, to ensure Tom doesn’t harm Daisy.

Nick, peering through a window, sees Tom and Daisy seated in their kitchen over cold fried chicken and ale. They aren’t happy, but there’s an “unmistakable air of natural intimacy” as they appear to be “conspiring together.” Disillusioned by their callous self-preservation, Nick leaves Gatsby alone, “watching over nothing.”

Chapter 7 Analysis: The Catastrophic Climax – Dreams Shattered, Illusions Exposed

Chapter 7’s oppressive heat is more than a backdrop; it becomes the crucible in which Gatsby’s meticulously constructed dream, Daisy’s fragile resolve, and the violent hypocrisies of the elite are brought to an explosive, tragic boil.

This chapter marks the novel’s devastating climax, exposing the brutal consequences of unattainable desire and moral bankruptcy.

The Unbearable Heat: Symbolism of Suffocating Truths

The “broiling” heat pervading Chapter 7 is a potent symbol, intensifying the characters’ agitation and mirroring the summer’s unresolved, simmering tensions.

Fitzgerald uses visceral descriptions of physical discomfort, Nick’s “damp snake” of underwear climbing his legs, the general irritability to show how the oppressive atmosphere strips social veneers and forces uncomfortable truths to the surface.

The heat isn’t merely weather; it’s a physical manifestation of the inescapable, suffocating reality closing in on Gatsby’s fragile dream, making polite pretenses unbearable and confrontations inevitable.

The Plaza Confrontation: Deconstructing Gatsby’s Facade

The Plaza Hotel suite transforms into an arena where Tom Buchanan systematically deconstructs Gatsby’s meticulously crafted persona with brutal precision. Tom’s aggressive challenges to Gatsby’s “old sport” affectation, his tenuous Oxford claim, and the illicit source of his wealth are calculated to expose Gatsby as an outsider and a fraud.

Gatsby’s initial assertion of control (“She never loved you”) crumbles as Daisy, under immense pressure, cannot bring herself to fully erase her past with Tom, admitting, “I did love him once, but I loved you too.” This admission is the true death knell for Gatsby’s specific, five-year-old version of the dream; Daisy cannot purely be the woman of his idealized memory.

Tom’s final revelation of Gatsby’s bootlegging and criminal connections utterly shatters Gatsby’s standing in Daisy’s eyes, leaving him exposed and his dream in ruins.

“Her Voice is Full of Money”: Daisy, Materialism, and the Impossible Choice

Gatsby’s iconic observation that Daisy’s voice is “full of money” reveals a profound understanding of her allure and essence. For Gatsby, her voice, with its “jingle” and “cymbals’ song,” embodies the “inexhaustible charm” of the old-money world he desperately wishes to penetrate. It signifies her class, effortless grace, and the security that wealth provides.

Daisy’s earlier comment, comparing Gatsby to an “advertisement” when she exclaims, “You always look so cool,” while seemingly affectionate, also hints at a perception of romance and allure through a lens of desirable commodities.

Ultimately, Daisy retreats when forced to choose between Gatsby’s passionate, but illicitly funded, dream and Tom’s established, secure fortune and social position. Her fear and withdrawal demonstrate that her romantic inclinations cannot overcome her deeply ingrained need for the safety and legitimacy of her class. (This was foreshadowed in chapter 4 with the story of marrying Tom despite Gatsby’s letter)

The Yellow Car: Symbol of Reckless Dreams and Death

Gatsby’s opulent yellow car, initially a vibrant symbol of his new wealth and a key instrument in his pursuit of Daisy, undergoes a grim transformation in Chapter 7, becoming the “death car.” Its flamboyant color, once representing hope and status, becomes irrevocably linked to recklessness and tragedy.

The tragic irony is searing: Myrtle Wilson, mistaking the approaching yellow car for Tom’s (who had driven it earlier), runs towards it seeking either confrontation or escape, only to be struck down by Daisy.

Daisy’s driving, and then not stopping, crystallizes her carelessness and inability to face consequences, immediately allowing Gatsby to shield her by claiming responsibility. The car, central to achieving Gatsby’s dream, becomes the agent of its violent, irreversible unraveling.

Moral Wasteland Revisited: The Eyes of Eckleburg & Wilson’s Grief

The chapter returns the narrative to the desolate valley of ashes, perpetually overseen by the giant, fading eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg. Myrtle’s violent death in this grim setting underscores the tragic consequences of the wealthy elite’s careless actions upon the lives of the less fortunate.

George Wilson, previously depicted as “spiritless” and “anaemic,” is transformed by his grief and dawning suspicion into a figure of chilling intensity. His sickness is palpable, a physical manifestation of his world collapsing.

Eckleburg’s eyes, a commercial remnant, watch over this tragedy. While Nick and Michaelis perceive them as a faded advertisement, Wilson, in his despair, later interprets them as the all-seeing eyes of God, highlighting the desperate human need for meaning and judgment in a seemingly godless, morally decaying landscape.

Tom’s subsequent, cruel manipulation of Wilson’s grief, subtly directing him towards Gatsby, further exemplifies this moral vacuum.

Nick’s Disillusionment: The 30th Birthday and “Conspiring Together”

Amidst the Plaza confrontation’s emotional wreckage, Nick’s sudden recollection of his 30th birthday, “Before me stretched the portentous, menacing road of a new decade”, marks a symbolic turning point. It signifies a loss of youthful idealism and an unwilling entry into a more cynical understanding of the world.

His revulsion culminates in his final observation of Tom and Daisy in their kitchen. Their “unmistakable air of natural intimacy” as they sit over plain cold fried chicken and ale, a simple meal contrasting with their usual opulent lifestyle, while “conspiring together,” reveals their chilling ability to retreat into their shared wealth and class.

In this crisis, they don’t use their immense riches for lavish enjoyment but as an impenetrable shield, protecting their status and insulating them from the devastating consequences of their carelessness.

This scene cements Nick’s profound disillusionment with the East and its inhabitants, ultimately fueling his decision to return West.

Gatsby’s Tragic Nobility?: Love, Loyalty, and Self-Deception

Gatsby’s immediate decision to take the blame for Myrtle’s death, despite Daisy being the driver, is a complex act. It can be interpreted as a final, grand gesture of his unwavering love and loyalty, a desperate attempt to protect Daisy at any cost.

This choice underscores a certain nobility within his deeply flawed character. However, it also reflects the full extent of his self-deception, a tragic clinging to the shattered illusion of their bond even as Daisy has effectively chosen Tom and retreated into their shared, insulated world.

His lonely vigil outside her house, “watching over nothing,” poignantly illustrates the utter emptiness of his dream once it has been irrevocably confronted by brutal reality.

Chapter 7: The Catastrophic Unraveling

Chapter 7 orchestrates the violent disintegration of Gatsby’s meticulously constructed dream. The intense confrontations strip away all facades, revealing the brutal realities of class, the hollowness of materialism, and the impossibility of genuinely repeating the past.

Fitzgerald uses the oppressive heat, the symbolic trajectory of the yellow car, and the tragic death of Myrtle Wilson to escalate the narrative to its catastrophic climax.

Gatsby’s idealized vision of Daisy shatters against her palpable fear and ingrained loyalty to Tom’s world of established wealth and social capital. Fitzgerald masterfully orchestrates this collapse:

- Tom reasserts his dominance through brutal social power and accusation

- Daisy retreats into the familiar security of her marriage, unwilling or unable to abandon its protections

- Gatsby’s dream, predicated on erasing the past, proves fatally incompatible with present reality

- Nick, marking a personal milestone, confronts a moral disillusionment with these characters and the society they embody.

With Gatsby’s dream shattered and tragedy unleashed, the narrative moves towards its somber resolution. Discover the fallout in our upcoming Chapter 8 analysis, or revisit the novel’s thematic currents in the main The Great Gatsby analysis.

A Note on Page Numbers & Edition:

Just as the events of Chapter 7 irrevocably alter the characters’ lives, ensuring citation accuracy requires careful attention to the specific text. We meticulously sourced textual references for this summary and analysis from The Great Gatsby, Scribner 2020 Paperback edition (Publication Date: September 1, 2020), ISBN-13: 978-1982149482. Always verify page numbers against your specific copy for academic integrity.