In the grand, chaotic theater of Jay Gatsby’s mansion, amidst the “men and girls [who] came and went like moths,” one figure lingers long after the music stops: Ewing Klipspringer, known simply as “the boarder.”

He’s a man who came to a party and seemingly never left. While often dismissed as a mere freeloader, Klipspringer is one of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s most chilling symbols in The Great Gatsby, an embodiment of the Jazz Age’s superficiality and moral emptiness.

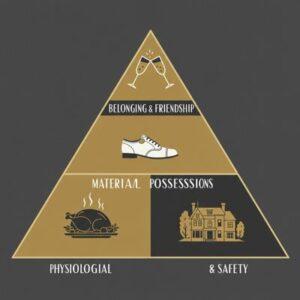

Our Ageless Investing character analysis of Ewing Klipspringer argues he’s more than a simple parasite; he represents arrested psychological development, a character perpetually stuck at the most basic levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

His actions, culminating in the infamous phone call for his tennis shoes, reveal a “survival mindset” that renders him morally blind to higher social obligations such as loyalty, gratitude, or empathy.

By analyzing his limited but notorious appearances through this unique psychological framework, we can understand him as a powerful symbol of the hollow core within Gatsby’s spectacular world. For essential plot context, you may first consult our summary of The Great Gatsby.

Note: Our analysis delves into Ewing Klipspringer’s appearances and symbolic role in The Great Gatsby and will necessarily discuss plot developments related to Gatsby’s parties and funeral. Reader discretion is advised if you have not yet completed the book.

“The Boarder”: Klipspringer as a Symbol of Jazz Age Superficiality

Nick first introduces Klipspringer not by his personality, but by his function: he’s “the boarder,” a man who came to a party and stayed. In this section, we’ll analyze his role as the ultimate party guest, showing how his presence and actions embody the transactional and superficial relationships in Gatsby’s social circle.

A Permanent Guest: The Nature of Parasitic Existence

Ewing Klipspringer’s status as “the boarder” immediately establishes him as a symbol of the parasitic element that Gatsby’s unvetted generosity attracts. Nick Carraway explains his presence with a note of dry amusement: “A man named Klipspringer was there so often and so long that he became known as ‘the boarder’—I doubt if he had any other home” [Chapter 4. Pages 61, 62].

Klipspringer is unlike the other partygoers, fleeting like “moths” and the important names that attend. He’s the only guest who’s defined not by who he is, but by what he takes from his host: lodging, food, and proximity to luxury.

He represents the logical endpoint of the transactional relationships on display at West Egg, where guests consume Gatsby’s hospitality without offering a genuine connection in return. Klipspringer has perfected this exchange, making it his lifestyle.

The Reluctant Performer: Music, Obligation, and Transaction

Klipspringer’s reluctant piano playing during Daisy’s reunion with Gatsby in Chapter 5 reveals his view of social interaction as purely transactional; he’ll perform a service only when directly commanded, not out of friendship or a desire to please.

When Gatsby asks him to play, Klipspringer demurs with weak excuses: “‘I don’t play well. I don’t—I hardly play at all. I’m all out of prac——‘” [Chapter 5, Page 94]. It takes Gatsby’s curt command, “‘Don’t talk so much, old sport… Play!’” [Chapter 5, Page 95], to get him to perform.

The scene is laden with irony as he plays “Ain’t We Got Fun,” a song whose lyrics, “One thing’s sure and nothing’s surer / The rich get richer and the poor get—children,” is a cynical commentary on the very class dynamics at play in the room. His detached, obligatory performance of sentimental love songs for Gatsby and Daisy emphasizes his lack of genuine emotional investment, reinforcing his role as a hired hand rather than a friend.

A Psychology of Survival: Analyzing Klipspringer through Maslow’s Hierarchy

Dismissing Klipspringer as merely selfish misses a deeper, more chilling interpretation of his character. By applying the psychological framework of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, we can understand his actions not as malicious but as the product of a psyche arrested at the most fundamental levels of survival, rendering him morally blind to the world around him.

The Foundational Needs: Shelter, Sustenance, and Liver Exercises

Klipspringer’s entire existence at the mansion is focused on satisfying his most basic needs, as defined by the foundational levels of Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy: physiological and safety needs. His status as “the boarder” directly fulfills his need for shelter. His constant presence ensures access to food and drink, with Nick even noting him “wandering hungrily about the beach” one morning [Chapter 5, Page 91].

His behavior reflects a man preoccupied with securing these essentials. Even his seemingly bizarre actions fit within this framework.

When Nick and Gatsby intrude upon his room, they find him “in pajamas… doing liver exercises on the floor” [Chapter 5, Page 91]. In the 1920s, “liver exercises” were simple calisthenics such as torso twists or leg raises, believed to stimulate internal organs and counteract the effects of a rich diet and sedentary lifestyle.

This detail, often overlooked, is not just eccentricity; it’s an action focused purely on maintaining the physical self, the absolute base level of the pyramid. His life is a closed loop of securing shelter, seeking food, and performing basic bodily maintenance, with little energy left for higher aspirations.

The Tennis Shoes: A Case Study in Arrested Development and Moral Blindness

The Great Gatsby is filled with disruptive telephone conversations, and perhaps the most infamous phone call in literature occurs in chapter 9. Klipspringer’s phone call in Chapter 9 is the ultimate textual evidence of a consciousness that cannot process higher-level needs such as loyalty, grief, or social duty because it’s fixated on practical, lower-level concerns.

When Klipspringer calls and Nick asks him about Gatsby’s funeral, Klipspringer’s response is a masterpiece of evasion, blaming a “picnic or something” in Greenwich for his inability to attend. He then pivots to his true purpose: “‘What I called up about was a pair of shoes I left there… I wonder if it’d be too much trouble to have the butler send them on. You see they’re tennis shoes and I’m sort of helpless without them’” [Chapter 9, Page 169].

From the perspective of Maslow’s hierarchy, this isn’t merely selfishness; Klipspringer displays arrested development.

For a psyche operating in “survival mode,” higher-level needs like belonging (attending a funeral) or esteem (showing respect) are incomprehensible when a lower-level safety or physiological need, a practical tool like shoes for mobility or social acceptance in a new setting, feels pressing.

His claim of being “helpless” without his shoes reveals his entire worldview: his security is tied to tangible objects, not abstract social bonds. This is the source of his moral blindness. He isn’t intentionally cruel; he’s psychologically incapable of perceiving the funeral’s significance because his mental resources are entirely devoted to securing his basic comfort and safety.

This psychological gap leads to Nick’s disgusted reaction of hanging up the receiver. While Nick operates on a higher level of the hierarchy, concerned with loyalty, respect for the dead, and social decency, Klipspringer operates on the most basic level.

Was Nick’s reaction unfair? Perhaps. In that moment, neither man could truly understand the other’s pressing needs. Klipspringer was incapable of comprehending Nick’s moral indignation, and Nick, in his grief and disillusionment, was unable to see Klipspringer not as a callous friend but as a creature of pure, unthinking survival instinct. The disconnect is total, highlighting the deep isolation between individuals living on different planes of human need.

Klipspringer’s Narrative Function: The Ironic Soundtrack and a Final Betrayal

Beyond his psychological profile, Klipspringer serves a crucial narrative and thematic function for Fitzgerald. He provides the ironic soundtrack to Gatsby’s romantic illusion and delivers the final, quiet betrayal that confirms the emptiness of Gatsby’s social world.

The Ironic Accompanist: The Meaning of “Ain’t We Got Fun”

The music Klipspringer plays provides a deeply ironic commentary on the events unfolding between Gatsby and Daisy in Chapter 5.

As Gatsby showcases his immense wealth, attempting to win Daisy with a spectacle of material success, Klipspringer reluctantly plays “Ain’t We Got Fun.” The song’s lyrics, which Fitzgerald explicitly includes, “One thing’s sure and nothing’s surer / The rich get richer and the poor get—children,” are a cynical anthem of class disparity.

Including these lines in the soundtrack to Gatsby’s romantic climax creates a biting narrative irony. It underscores the transactional and materialistic underpinnings of the very world Gatsby has constructed, capturing what he believes is a pure, romantic ideal. It’s a critique that Klipspringer, in his detached performance, is perfectly suited to deliver.

The Final Freeloader: A Study in Survivalist Indifference

Klipspringer’s final phone call solidifies his role as the ultimate symbol of the transactional, superficial nature of the hundreds of guests who used Gatsby for his hospitality. His character is best understood when contrasted with the novel’s other peripheral figures who react to Gatsby’s death.

While the eccentric observer known as Owl Eyes also partook in the parties, his sober attendance at the funeral shows a capacity for genuine perception and empathy, acknowledging the “poor son-of-a-bitch” [Chapter 9, Page 175]. Klipspringer’s absence, because of a vague social engagement and a need for his tennis shoes, represents the final, logical outcome for a purely parasitic relationship.

This self-preservation can be further contrasted with that of another figure who benefited from and ultimately abandoned Gatsby: the formidable Meyer Wolfsheim.

Wolfsheim’s refusal to attend the funeral is a calculated, professional decision rooted in a cynical but coherent underworld philosophy: “Let us learn to show our friendship for a man when he is alive and not after he is dead” [Chapter 9, Page 172]. It’s the cold pragmatism of a predator cutting ties with a compromised asset.

But Klipspringer’s indifference lacks even this cynical logic. It’s more fundamental, almost thoughtless—the instinct of a creature seeking its next warm burrow, unconcerned with the fate of its former shelter. He’s the ghost of parties past, the embodiment of an entire social circle that consumed Gatsby’s generosity but felt no human connection, proving in the end that Gatsby, for all his crowds, was utterly and tragically alone.

The Hollow Man of a Hollow Age

Ewing Klipspringer, “the boarder,” is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterfully subtle portrait of moral emptiness in The Great Gatsby. He’s a man so completely defined by his basic needs for comfort and security that he becomes a ghost in his own life, incapable of loyalty, gratitude, or genuine human connection.

Through the unique psychological lens of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, his infamous call for his tennis shoes transforms from a simple act of selfishness into a profound symptom of arrested development, the moral blindness of a man perpetually stuck in a state of survival mode.

As the ironic accompanist to Gatsby’s grand romance and the final, casual betrayer of his host, Klipspringer is a chilling symbol for the superficiality of the entire Jazz Age world Gatsby tried so desperately to conquer.

The guest who took advantage of Gatsby’s hospitality the most revealed the hollowness that lies beneath the era’s glittering facade. It reminds us that extravagant hospitality cannot purchase friendship, and that a life dedicated solely to self-preservation leaves no room for a soul.

To explore the world Klipspringer inhabited, see our complete analysis of the man who gave Klipspringer shelter, Jay Gatsby.

A Note on Page Numbers & Edition:

We carefully sourced textual references for this analysis from The Great Gatsby: The Only Authorized Edition (Scribner, November 17, 2020), ISBN-13: 978-1982149482. Just as Klipspringer was concerned with his own tangible possessions, page numbers for specific events can differ across various printings. Always double-check against your copy to ensure accuracy for essays or citations.