In the final pages of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, after the last party guest departs, Henry C. Gatz arrives from Minnesota, a figure from a past his son sought to escape.

As Gatsby’s estranged father, his brief, grief-stricken appearance grounds the magnificent myth of “Jay Gatsby” in the humble, human reality of “Jimmy Gatz.” He offers a profound commentary on ambition, family, and the American Dream.

Our Ageless Investing character analysis of Henry C. Gatz argues that he’s a crucial thematic figure whose pride and traditional values provide a tragic counterpoint to his son’s world.

We contend that Mr. Gatz embodies a disciplined, older version of the American Dream, and his naive perception of Gatsby’s success crystallizes Fitzgerald’s critique of the Jazz Age’s corrupting influence and the profound isolation born of radical self-invention.

Through examining his poignant words and the artifacts he carries, we illuminate the origins of Gatsby’s ambition and the ultimate cost of his transformation. For essential plot context, please first consult our summary of The Great Gatsby.

Note: Our analysis delves into Henry C. Gatz’s appearance and symbolic role in The Great Gatsby and will necessarily discuss plot developments related to Gatsby’s death and funeral. Reader discretion is advised if you have not yet completed the book.

The Father from the Past: Henry Gatz’s Arrival and Poignant Reality

When Henry C. Gatz arrives at his son’s opulent mansion in Chapter 9, his presence immediately shatters the carefully constructed myth of Jay Gatsby. In this section, we analyze his initial portrayal and what his simple, grief-stricken character reveals about the humble world his son so desperately sought to escape.

A Man Out of Place: The Contrast Between Father and Mansion

Fitzgerald emphasizes the almost painful contrast between Mr. Gatz and the lavish environment his son created. Nick Carraway describes him as “a solemn old man very helpless and dismayed, bundled up in a long cheap ulster against the warm September day” [Chapter 9, Page 167].

This image of a man in a “cheap ulster,” ill-suited for the weather and dwarfed by the splendor of the mansion, immediately establishes him as an outsider in his own son’s world. His grief is palpable; his hand trembles so much that a “glass of milk spilled” [Chapter 9, Page 167]. Yet, as he beholds the mansion, his grief “began to be mixed with an awed pride” [Chapter 9, Page 168].

This juxtaposition of simple, humble grief with awe at material success highlights the vast gulf between Gatsby’s origins and his created persona, underscoring the completeness of his son’s transformation.

The Unknowing Witness: Mr. Gatz’s Perception of Gatsby’s Life

Henry Gatz’s dialogue with Nick reveals a profound, almost willful, naivete about his son’s life and the source of his wealth. He proudly tells Nick, “‘Jimmy always liked it better down East. He rose up to his position in the East’” [Chapter 9, Page 168].

He sees Gatsby’s life as a straightforward success story, a validation of potential. He carries a “dirty” photograph of the house, which Nick suspects “was more real to him now than the house itself” [Chapter 9, Page 172], suggesting Mr. Gatz has clung to the image of his son’s success rather than its complex and corrupt reality. He seems entirely unaware of the bootlegging or the obsessive love for a married woman that financed the mansion in the photograph.

This perception is a tragic counterpoint to what the reader knows, highlighting not only Gatsby’s success in curating his image but also the deep communication gap between a father rooted in traditional values and a son immersed in the moral ambiguities of the Jazz Age.

A Blueprint for Success: The “Hopalong Cassidy” Schedule and a Different American Dream

The most significant insight Henry Gatz provides comes from a single, powerful artifact: his son’s boyhood copy of ‘Hopalong Cassidy.’ In this section, we analyze the detailed schedule found within, arguing it represents a more traditional, disciplined, and tragically abandoned path to the American Dream.

The Schedule: A Testament to Early Ambition and Discipline

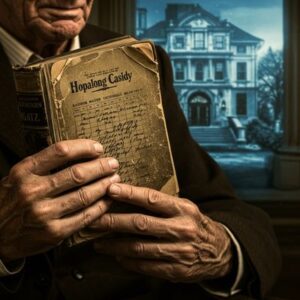

From his worn wallet, Mr. Gatz produces a “ragged old copy” of ‘Hopalong Cassidy’ and proudly shows Nick the last fly-leaf. On it, a young Jimmy Gatz had meticulously planned his path to self-improvement.

The “SCHEDULE,” dated 1906, details a rigorous routine that contrasts with the decadent leisure of Gatsby’s later life: “Rise from bed … 6.00 A.M. Dumbbell exercise and wall-scaling … Study electricity, etc … Practice elocution, poise and how to attain it… Study needed inventions…” [Chapter 9, Page 173].

This artifact reveals that Gatsby’s ambition was not born in a moment but was a foundational part of his character from a young age. It reflects a classic, Ben Franklin-esque model of the American Dream, one based on discipline and tangible effort, a world away from the “easy money” and moral shortcuts of the bootlegging era.

The “GENERAL RESOLVES”: An Early Moral Compass

Listed beneath the demanding schedule is a set of “GENERAL RESOLVES” that establish an early moral framework for James Gatz, one that his later persona would largely abandon. The resolutions include “No wasting time… No more smokeing or chewing… Be better to parents” [Chapter 9, Page 173]. The irony of these intentions, particularly “Be better to parents,” hangs heavily in the air, given Gatsby’s subsequent estrangement.

This list powerfully humanizes Gatsby, revealing the earnest, striving boy he once was before dedicating himself to the “service of a vast, vulgar, and meretricious beauty” [Chapter 6, Page 98]. It provides a tragic baseline against which the moral compromises of his adult life can be measured.

A Father’s Pride: Mr. Gatz’s Interpretation of the Evidence

For Henry Gatz, the schedule is definitive proof of his son’s inherent greatness. He presents it to Nick with earnest pride, insisting, “‘It just shows you, don’t it?’” and “‘Jimmy was bound to get ahead. He always had some resolves like this or something’” [Chapter 9, Page 173]. Mr. Gatz sees the potential and the discipline as the achievement itself. His interpretation is untroubled by the moral complexities of how that ambition was later realized.

For him, this tattered piece of paper validates his son’s entire life, proving that “Jimmy” was always bound for greatness. This highlights a generational perspective where evidence of hard work is seen as more significant than the morally ambiguous results of that work.

Pride, Grief, and Delusion: Analyzing Mr. Gatz’s Perception of His Son

Henry Gatz’s perception of his son is a complex mixture of awed pride in his material success and a deep, often uncomprehending, grief. In this section, we explore his psychological state, connecting it to academic interpretations of the American Dream and paternal relationships.

The Modern Robber Baron: Mr. Gatz’s Comparison of Gatsby to James J. Hill

Henry Gatz’s perception of his son’s success is filtered through an older, more traditional lens of American ambition. He proudly tells Nick, “‘If he’d of lived he’d of been a great man. A man like James J. Hill. He’d of helped build up the country’” [Chapter 9, Page 168].

As academic critics have noted, this comparison is deeply revealing. One such analysis from the F. Scott Fitzgerald Review highlights how this positions “Gatsby as a self-made man and suggests his equivalency to major industrialist robber barons such as Hill” (Jay Gatsby and the Prohibition Gangster as Businessman).

By equating Gatsby—a bootlegger and front for a criminal syndicate—with a figure of national industrial might, Mr. Gatz displays a profound misunderstanding of the Jazz Age’s new, often illicit, pathways to wealth.

His statement highlights a generational gap in the very definition of the American Dream, where he sees his son’s wealth through a mythologized lens of industrial contribution. He’s unable to see the corrupt reality behind the facade.

The Absent Father, The Spiritual Son

Henry Gatz’s late appearance underscores his functional absence throughout Gatsby’s life of reinvention. Gatsby effectively shed his biological father in favor of self-creation and practical “fathers” like Dan Cody.

Some critical interpretations, such as one explored in the F. Scott Fitzgerald Review, have drawn parallels between the novel and Homer’s Odyssey, framing Nick Carraway as a “Telemachus, the son in search of his father” (Nick Carraway as Telemachus: Homeric Influences and Narrative Bias in The Great Gatsby).

In this reading, Nick finds that his spiritual father is not a traditional figure, but in Jay Gatsby, the man of the “incorruptible dream.”

Within this lens, Henry Gatz’s appearance at the end is a tragic reminder of the biological paternity that Gatsby rejected. He’s the father left behind, a testament to the paternal void at the heart of Gatsby’s constructed identity, a void Gatsby himself could never fill, even as he became a figure of fascination for Nick.

Pride as a Shield Against a Corrupt Reality

Henry Gatz’s overwhelming pride in Gatsby’s mansion and ambition can be interpreted as a psychological shield. It allows him to focus on the symbols of his son’s success while remaining willfully ignorant of the criminal means used to achieve them.

His grief is real, but it is “mixed with an awed pride” [Chapter 9, Page 168]. This focus on the magnificent house and boyhood dreams allows him to avoid confronting the uncomfortable truths of Gatsby’s life as a bootlegger and his obsessive pursuit of a married woman.

In a way that resonates with modern cultural discussions about curated online lives, Mr. Gatz is like a parent celebrating a child’s glamorous social media presence, immensely proud of the beautiful facade without understanding the complex reality beneath the surface. His pride is both genuine and a form of protective delusion.

The Thematic Significance of Henry Gatz: Grounding the Myth

Though his role is brief, Henry C. Gatz is thematically crucial. His presence provides a grounding reality that gives Gatsby’s spectacular myth its tragic weight and poignancy. In this section, we analyze his ultimate importance to Fitzgerald’s social critique.

Symbol of the Midwest and the Inescapable Past

Mr. Gatz represents the humble, authentic, and perhaps naive Midwestern past that Jay Gatsby both sprang from and so desperately tried to erase.

His simple attire (“long cheap ulster”), unadorned grief, and physical presence from Minnesota in the heart of East Coast opulence are a harsh reminder of Gatsby’s origins.

While Gatsby tried to invent a new past for himself, his father’s arrival proves that you can never fully shed the past. Henry C. Gatz is the living embodiment of the “James Gatz” that “Jay Gatsby” attempted to destroy, and his presence makes Gatsby’s transformation all the more remarkable and more tragic.

The Failure of Communication and the Tragedy of Isolation

The relationship between Henry and his son underscores a central theme of the novel: the failure of authentic communication, particularly across divides of class, experience, and ambition.

Gatsby’s estrangement from his father reveals the depth of this disconnect. Mr. Gatz’s incomplete and romanticized understanding of his son’s life further highlights this communication gap. His poignant presence at the nearly empty funeral emphasizes Gatsby’s ultimate isolation; even his father, who genuinely loved and admired him, never truly knew the man his son had become.

This failure of familial connection adds a layer of deep personal tragedy to Gatsby’s public downfall. It reveals that in his quest to win the world, he lost the simple, authentic bond of family.

The Grieving Father of an American Illusion

Henry C. Gatz, in his brief and sorrowful appearance in The Great Gatsby, provides a profound, humanizing counterpoint to his son’s spectacular myth. He’s the ghost of a simpler, more traditional American Dream, a man whose quiet pride and poignant grief ground Gatsby’s grand illusion in a humble reality.

Through the boyhood schedule of disciplined ambition he so reverently carries, he reveals the earnest origins of the man who would become Jay Gatsby, making his son’s later moral compromises and ultimate destruction all the more heartbreaking.

More than just a grieving father, Mr. Gatz symbolizes the inescapable past and the isolation that results from radical self-invention. His naive admiration for Gatsby’s material success highlights an unbridgeable generational gap and serves as Fitzgerald’s final critique of the Jazz Age’s corrupting definition of achievement.

Ultimately, the presence of Henry Gatz at his son’s empty funeral is a devastating reminder of what Gatsby sacrificed—not just his life, but his authentic connections to family and origin—in his relentless pursuit of a beautiful, yet unattainable, illusion.

To explore the world through the eyes of Gatsby’s father and son, see our collection of Jay Gatsby quotes with analysis.

A Note on Page Numbers & Edition:

We carefully sourced textual references for this analysis from The Great Gatsby: The Only Authorized Edition (Scribner, November 17, 2020), ISBN-13: 978-1982149482. Just as Henry C. Gatz held a photograph representing a reality he couldn’t fully comprehend, page numbers for specific events can differ across various printings. Always double-check against your copy to ensure accuracy for essays or citations.